This is a subject close to my heart as a member of my close family recently gave birth to a so-called “overdue baby” at 42 weeks and one day.

Although here in the UK anything between 38 and 42 weeks is considered a perfectly normal and natural gestational term (40 weeks being considered “on time”), she had endured weeks of pressure from midwives and consultants to agree to them artificially inducing labour. Towards the end she was becoming increasingly stressed and distressed at the amount of coercion she was experiencing. Her first baby had been medically induced and the birth ended traumatically, and this time around she was determined she was going to let her little girl come in her own sweet time. She stuck to her principles and her maternal instinct that told her her baby was doing perfectly fine despite the scare tactics some staff were using.

It turned out that babe only needed one extra day in the proverbial oven before she was ready to come and meet the world, but her poor mother had to spend her final weeks of pregnancy fending off what was on the edge of becoming actual harassment from medical staff desperate to get her baby out ASAP. This was not an entirely risk free pregnancy, but there was no medical emergency or indication that either mum or baby were in immediate danger, so why all the pressure? She was highly informed, aware of the risks and very clear in her desire to wait until the full 42 weeks before even considering induction, so why did she have to put up with her last weeks of pregnancy being the most stressful of her life? Let’s take a look at some of the facts behind inducing labour with an “overdue baby” (I can’t make those quotation marks big enough, by the way!).

Disclaimer: I am not a medical practitioner and this blog should NOT be taken as medical advice. You should always ask for as many professional, medical opinions as possible before making any final decisions about induction (please see full disclosure HERE). The information in this blog assumes that your pregnancy is low risk and free from any complications or signs of risk indicators such as pre-eclampsia or placental abruption. If you have had any unusual symptoms during your pregnancy, discuss them with your care provider. Ensure you are familiar with the signs and symptoms of a possible stillbirth and, in particular, always contact your care provider immediately if you feel your baby’s movements change from their usual routine. Please see the Kicks Count website and accompanying app for more information.

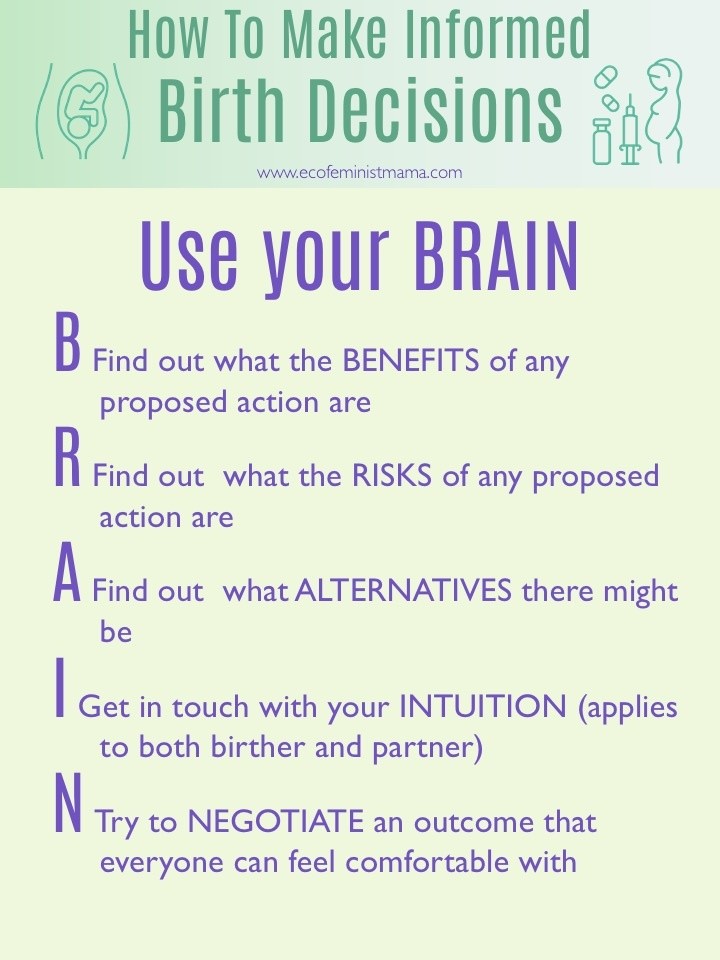

Finally, please always use the BRAIN acronym when making any decisions about pregnancy interventions:

Table of Contents

Why do babies go “overdue”?

The reasons behind a pregnancy going over 42 weeks and becoming referred to as “overdue” (I will use the phrase “post-term”) are usually unknown. Often women whose mothers, sisters or other close female relatives have had a post-term pregnancy are more likely to have one, so genetics may play a part. Other factors that may make a post-term pregnancy more likely are a previous post-term pregnancy, and older women may also be more likely to go over 42 weeks.

All that said, I personally feel we should be questioning the very idea that a baby is “due” on any particular day and can therefore be OVERdue at all. One study in 2013 found such huge variables in the average pregnancy term that they concluded the term “due date” should be scrapped in favour of offering a range of dates in which the baby can be expected to make an appearance. Given that the calculations used to predict a “due date” (again, heavy quotation marks here – you can probably tell by now I hate this concept of baby due-ness!) are based on a dodgy calculation made back in the 18th century called Naegele’s Rule, we’re frankly OVERDUE for an update on the narrative surrounding the timing of a baby’s birth.

Why is induction recommended for an “overdue” baby?

In the case of an otherwise low-risk pregnancy with no complications so far, inductions are usually recommended for a prolonged pregnancy due to historical evidence that there is an increased risk of stillbirth after 42 weeks. This is most likely what you will be told is the reason for “needing” an induction.

Now, it is the case that some evidence suggests there may be a reduced risk of stillbirth if induction is accepted at 41 weeks, as opposed to carrying on past 42 weeks. In particular there is a famous Swedish study which was shut down early due to a small number of stillbirths (5 out of a group of 1,379 pregnancies) occurring in the expectant management (42 weeks plus) group, while none occurred in the induction at 41 weeks group. Of course, being an incomplete study the figures cannot be considered conclusive, but the reasons for stopping the trial obviously caused concern.

What is less well known, however, is that a Danish study that WAS completed showed no difference in the number of stillbirths or perinatal deaths in pregnancies that were induced at 41 weeks compared to 42 weeks. This is incredibly important information, since it is the Swedish study that generally gets brought up with women during conversations about preterm induction, and yet the Danish study concludes that there is no increased risk when reaching 42 weeks. Having access to that information could make all the difference for a woman unsure about whether to accept induction at 41 weeks or give her body and baby another week or more to do things naturally.

EDIT 4th August 2020: Though the risk of stillbirth is small, the grief and pain caused to those who have to endure it is immeasurable. It is vital that, if you are considering declining an induction, you familiarise yourself with the signs and symptoms of a possible stillbirth and ensure you immediately report any changes in your baby’s movements to your care providers. Shortly after originally publishing this blog, I was contacted by a wonderful woman called Miranda, who sadly had to endure every mother’s worst nightmare when her son lost his life in the womb. She had experienced a number of small but, it turns out, crucial symptoms during her pregnancy that were not picked up on by her healthcare team. Sadly, if they had been, it’s very possible that an induction could have saved her precious son. It is important that we recognise the true human cost behind the studies and statistics and not be complacent when we see these figures. In order to help you reach the most appropriate decision for you and your baby, I would like to make sure that Miranda’s voice and her son Adrian’s story are heard – please visit her blog to read their story and hear another perspective on this subject.

One of the things that struck me when I read her blog was how part of her felt as though something was not quite right, and yet her care providers didn’t take her concerns seriously. Just as expectant mothers have the right to decline interventions we feel are unnecessary, and have our voices heard when we say no, we should also make sure that our concerns and instinctive sense of something being wrong are listened to and taken seriously.

Another reason induction is often recommended is if medical staff believe the baby is getting “too big” (fetal macrosomia, in medical language) and therefore the mother will struggle to deliver safely. Firstly, the NICE guidelines on inducing labour state quite clearly that induction should not be performed solely for this reason in the case of an otherwise healthy pregnancy:

1.2.10.1 In the absence of any other indications, induction of labour should not be carried out simply because a healthcare professional suspects a baby is large for gestational age (macrosomic).

Although with larger babies there is an increased risk of shoulder dystocia (baby getting stuck around the shoulders – this happened to me, by the way, but my mother and I were both fine afterwards), inducing a larger baby also increases the risk of severe perineal trauma. If the natural process of the body interrupted, it seems the body will struggle more to do what it needs to do to deliver a larger baby. Furthermore, growth scans are notoriously inaccurate, with a whopping 15% margin of error either way, so your baby may not actually be all that big anyway! On top of all that, the idea that the female body can create a baby that is “too big” to give birth to without intervention has no basis in evidence at all, and I would argue is more down to the systemic mistrust of the female body that causes so many problems of sexism and misogyny in Western society.

Is it safe to go past 41 weeks pregnant?

Yes! Advocates of induction after 41 weeks often cite evidence such as the Swedish study mentioned above and the Cochrane review, arguing that the risks of a negative outcome increase after 41 weeks. However this risk increase still makes the chances of stillbirth tiny, with the numbers changing from 1 stillbirth out of 1,000 births in the case of induced labours to 2 out of 1,000 in the case of expectant management past 42 weeks. If your care provider tells you that the risk of you having a stillbirth will double if you go post-term, this is what they are referencing. Yes, they are correct in quoting this Cochrane review figure, but the chances are still very very small and need to be weighed up against the risks of the cascade of interventions and birth trauma associated with labour induction.

As a 2019 discussion paper into the levels of risk associated with routine induction puts it:

“…we argue that a small absolute increase in risk on its own, without any other medical risks or complications during pregnancy, does not justify a policy of routinely offering induction of labor without strong evidence of the benefits of that policy” Seijmonsbergen‐Schermers et al (2019)

In an otherwise healthy pregnancy, there is no reason why an induction should be routinely offered to a woman without any specific medical information and strong evidence suggesting that her pregnancy in particular is at risk of a stillbirth. Meanwhile, the negative outcomes associated with induction present a very real risk to both mother and baby and arguably should not be so eagerly encouraged.

Do I have to have an induction after 42 weeks?

No, no, no, no and, also, NO. So many women are under the false impression that you are obliged to take an induction after 42 weeks whether you want one or not. Of course, you may genuinely want one by that point and that’s your decision, but it is YOUR decision. You have the legal right to decline any and all medical treatment and interventions if you wish and that is quite simply the end of it.

I have heard an alarming number of women say they have been threatened with a referral to social services if they refuse an induction. This is absolutely unacceptable. If you have been given all the information regarding the potential risks of going post-term in your pregnancy, and you have the mental capacity to be able to make informed decisions about your own medical treatment, midwives and doctors cannot refer you to social services on the basis of your birth choices. Unless they have a specific reason to believe that you may harm you baby after it is born, they have no basis on which to call social services. Furthermore, this should not be used as a way to threaten, bully or attempt to coerce you into accepting an intervention you do not want. If you are experiencing this kind of bullying (and it IS bullying, even when it’s coming from a doctor) please contact Birthrights and AIMS to get the support you need to make a formal complaint. It may feel like the last thing you want to be doing in your final stages of pregnancy or early postpartum, but remember that people in powerful positions should not be allowed to abuse that power and other women deserve not to have to experience such unpleasant behaviour.

How do they induce labour?

The first step on the road to official labour induction is to be offered a membrane sweep, or cervical sweep. This is where a midwife or doctor will “sweep” their (gloved) finger around your cervix in an attempt to separate the membranes of the amniotic sac that surrounds your baby. This is often sold to women as a benign and minor intervention, but it is still a labour induction method. In theory, you’ll be offered a sweep at your 40 and 41 week maternity appointment if it’s your first baby, or just the 41 week one if you’ve had a baby before. In practice, though, there are midwives who will cheerily tell you at your 38 week appointment that they’re booking you in for your sweep as if it’s a done deal. I’ve heard this story come from women more than once and, although it’s often presented to them as a formality “Oh we can always cancel it later and I’m sure baby will arrive before then anyway”), it’s a slippery slope where women are nudged, or even coerced in the direction of an increasing number of interventions that they (mistakenly) believe they have to agree to. Remember, you can always refuse offers of medical treatment. ALWAYS.

The NHS website claims a membrane sweep is not painful, although one study showed that 70% of women described the procedure as bringing significant discomfort, with a third saying it was significantly painful, and there was an average pain rating of seven on a scale of one to ten (ten being the worst pain imaginable). The membrane separation helps to release prostaglandins, hormone-like compounds which are associated with the onset of labour (a synthetic version of prostaglandins is used in formal induction which we’ll discuss shortly).

Membrane sweeps (sometimes known as strips) are generally fairly low risk, but they are sometimes followed by bleeding and discomfort in the uterus, with irregular contractions (but not labour contractions) being a common occurrence. Another possible side effect of a membrane sweep is that it will trigger a premature (i.e. pre-labour) rupture of the amniotic sac surrounding your baby, leading to your waters breaking (one study found there was a one in ten chance of this happening). If labour doesn’t start within 24 hours of this occurring, the chances of needing to be induced in order to avoid harm go through the roof. Again, you don’t have to accept any offer of induction but you will make the medical staff very nervy if you say no and they’ll almost certainly put a lot of pressure on you to undergo intense monitoring at the very least.

While the risks around sweeps are low, and many consider them a relatively non-invasive and straightforward procedure, it’s important to remember that this IS an intervention into your and your baby’s natural processes and it is one of the early labour induction methods. Although you may be thoroughly fed up of being pregnant and tempted to accept the offer of “just a little sweep to get things moving”, it’s a significant interference and disruption to what your body is doing perfectly well of its’ own accord i.e. taking exactly the right amount of time it needs to grow a baby.

If you do choose to have a membrane sweep but don’t go into labour within a few days, you may be either offered another one or a full induction (the sweep being the amuse-bouche to the main event). This would have to be carried out in a hospital, so if you were planning a home birth you would need to abandon that plan (incidentally, I have an in-depth blog post on giving birth at home here if this is something you’re hoping to do).

To begin an induction, a synthetic version of prostaglandin is inserted into your vagina (either in a regular dose or as a “controlled release” version, which is slower to take effect) via a tablet, gel or pessary (a small, soluble block). The Tommy’s website says that these drugs, “act like the natural hormones that kick start labour”, implying that the beginning of labour via synthetic prostaglandins is similar to that of a natural start. However, induced labour is known to be more painful, more likely to lead to an epidural and more likely to result in an assisted delivery via either forceps or ventouse.

The introduction of synthetic hormones also interfere with the woman’s own hormone production and both the maternal body and unborn baby are essentially forced into beginning a process they weren’t actually ready for (if they were, labour would have started already!) In particular, the introduction of synthetic oxytocin (AKA pitocin, often brought into the induction process to speed up what is considered to be a “slow” labour) can have hugely detrimental effects on the body’s natural hormone production and interfere with mother-infant bonding and the establishment of breastfeeding.

What are the risks of being induced?

A Cochrane Review of the available evidence on the risks of induction concluded that it is associated with a higher likelihood of the use of forceps or ventouse in a vaginal delivery. Some studies showed a higher risk of postpartum haemorrhage and neonatal trauma, however the available evidence and overall figures suggested no solid link. A recent study however has shown that induction is associated with a higher risk of uterine ruptures due to the induction drug’s capacity to force the uterus into having strong contractions.

The main risk of induction, however, is that it often marks the beginning of a cascade of interventions in childbirth. When the body and baby aren’t ready to go into labour (which no test can check but, if there’s no baby yet, that’s a pretty good sign!) then forcing unnatural labour initiates a fundamental disconnect between what your body intends to do and what it is actually doing. An artificially induced start to labour is not the same as a spontaneous one and there’s no way to know that the body and baby will respond to that intervention positively. It may respond well enough if spontaneous labour was soon on the cards anyway, but very often one intervention often leads to another intervention, and another and another.

I want to be clear that a negative birth experience is by no means an inevitable fate when receiving an induction. There are positive induction stories out there and I encourage you to look for them so you can get a balanced view. However, for a great many women, inducing labour is the first of a series of escalating and perfectly avoidable medical interventions into birth, all happening under the fog of hormone-blocking drugs that make it more difficult for the birthing woman to give informed consent.

Not only that, often they’re not told the potential long-term possible consequences in terms of postpartum challenges and attachment struggles with their baby. I saw a post from one woman in a Facebook group who was incredibly depressed, expressing feelings of self-loathing and resentment towards her baby, as a direct result of not feeling bonded with her newborn. I asked if she’d had an epidural or narcotic pain relief, as these can interfere with the natural release of the bonding hormone oxytocin in the crucial moments after birth. “Oh my god, YES” was her answer and she described an escalating series of interventions and birth trauma that began with an induction. She had literally had no idea that accepting these interventions would put her baby’s attachment experience at risk and no-one had told her how to mitigate the risk by engaging in lots of skin-to-skin with her baby. It made me so sad that this lovely new mother had been having such a miserable time struggling to connect with her sweet little baby, and that she had blamed herself for being a bad mother when it was the result of the cascade of interventions associated with induction. Even just having that knowledge made her feel much better and she resolved to try and heal the attachment wound with as much skin-to-skin time with her baby as possible.

I don’t want to give you the impression that birth trauma and postnatal challenges are inevitable if you consent to inducing labour. My point is that, when you’re balancing up the risks associated with your different options, these are some of the risks you need to be considering.

How painful is it to be induced for labour?

Childbirth is painful however it begins, but induced labour is generally more painful than a spontaneous start. This is because the triggering of contractions causes them to come on much more quickly and the body (which remember isn’t expecting labour to start yet) doesn’t start to produce the natural pain-reducing hormones that it would if it was left to do things naturally. This is how the cascade of intervention in childbirth begins, since the additional pain often leads women to requesting an epidural or other forms of pain intervention, which cause problems of their own.

Why do doctors push induction?

I am sure that a great many, if not the majority, of doctors and midwives push induction because they genuinely believe it is the best and safest course of action to take. They will have become aware of studies like the Swedish one referenced earlier and the policies formed at their hospital and throughout the wider NHS Trust have likely convinced them that routine induction is the way forward.

However, without wishing to sport a tin foil hat, I do wonder whether the increasing number of inductions and the amount of extreme coercion I’ve heard about from women facing pressure to induce may have a further level of motivation. The fact is that the longer your pregnancy continues and the less predictable your birth date is, the more costly and potentially inconvenient your care becomes. The NHS maternity services in the UK are under intense pressure due to staff shortages and over a decade of Tory spending cuts and, as this report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows, induction of labour means that struggling maternity units (MUs) can delay and juggle admission dates to ease pressure on their resources, whereas they have no control over the admission date for a woman in spontaneous labour.

The same report discusses the fact that issues surrounding the number of hospital beds can be eased by “speeding up labour” via induction methods. Given that availability of beds, staff and general capacity regularly leads to MUs having to temporarily close their doors, it’s maybe not so cynical of me to think that inducing labour might be as much about convenience for MUs as it is about safety. I don’t want to imply that your doctor or midwife specifically is consciously and deliberately trying to bring your pregnancy to and end as soon as possible and speed up your birth date. However I do find the increasing number of routine inductions rather alarming and this is one more reason to question, not simply accept, your care provider’s insistence that you induce.

If you found this blog on inducing labour for an “overdue” baby helpful, please consider sharing it with others who might find it helpful too. Also, I would love to hear your empowering stories of saying no to inducing labour and having a positive birth, so please do get in touch and let me know if you would like to tell your birth story to other Ecofeminist Mamas!